Chicago’s Elevated Rapid Transit System: Tracking the Expansion of the “L”

Chicago has many distinguishing features that set it apart from other great cities. There’s the 26 miles of lakefront parks and beaches, world-class restaurants, landmark theaters, legendary professional sports, globally-inspired cultural events, and of course world-renowned architecture and commercial buildings.

Chicagoans often take these assets for granted. Yet, they all attract business and commerce, lure visitors and leaders from around the world, and collectively impact the overall economic viability of the city.

Another part of Chicago’s urban fabric literally stands above the downtown hustle and bustle, yet it also helps shape the central business district into a global center of commerce. We’re referring to the Chicago Transit Authority elevated rapid transit train, better known as the “L.”

The “L” is part of the rapid transit system that serves much of Chicago, and it constitutes the second-longest public transportation system in total track mileage in the United States. On average 703,326 people ride the “L” each weekday, making it the third-busiest rail mass transit system in the country. Last year alone, annual ridership was 221.6 million.

In a 2005 poll, Chicago Tribune readers voted the “L” as one of the “seven wonders of Chicago.” While the infrastructure and operations of the Chicago Transit Authority (CTA) are a wonder in itself, we’ll focus on the history of the “L” and how it affected Chicago’s development since its inception 120 years ago.

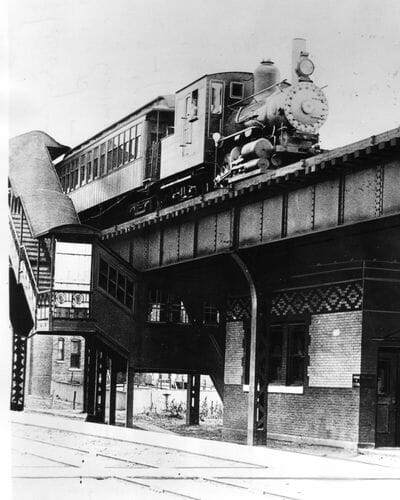

Consistent with Chicago’s history of economic development, the first “L” originated on Chicago’s South Side. On June 6, 1892, a small steam locomotive pulling four wooden coaches carrying a total of 27 men and three women departed the 39th Street Station and arrived at the Congress Street Terminal. The train ran on tracks that are part of today’s Green Line. This makes the “L” the second-oldest rapid transit system in the Americas. If you’d like to experience what it was like to ride on the very first “L,” stop by the Chicago History Museum’s “Crossroads of America” exhibit and climb aboard “L” Car No. 1.

As it is today, Chicago was considered a leader in technology innovation during the late nineteenth century. In 1895, the Metropolitan West Side Elevated (which had lines to Douglas Park, Garfield Park, Humboldt Park and Logan Square) was the nation’s first non-exhibition rapid transit system powered by electric traction motors. Two years later, the South Side “L” introduced multiple-unit control, in which several or all the cars in a train were motorized and under the operator’s control. Electrification and multiple-unit control are still standard features of most of the world’s rapid transit systems.

An early “L” train

While railway technology has remained relatively consistent in the past 100-plus years, one of the starkest differences between the early “L” and today is its role the Central Business District. At first, the “L” only served areas outside of Chicago’s CBD. Financier Charles Yerkes controlled much of the city’s early streetcar system, and obtained the necessary signatures to expand the railway system downtown. He did not want elevated railroads in the CBD, so it’s ironic that his greatest legacy to the city was The Loop — a rectangle of elevated tracks enclosing Chicago’s business district. Thanks to Yerkes, the Union Loop opened in 1897 and greatly increased the rapid transit system’s convenience.

In 1911, the “L” lines were obtained by Samuel Insull, president of the Chicago Edison electric utility (now Commonwealth Edison), who was interested in the fact that the trains were the city’s largest consumer of electricity. Insull instituted many improvements, including free transfers and through routing. He also bought other Chicago electrified railroads, and ran the Chicago North Shore and Milwaukee Railroad lines to downtown Chicago via the “L” tracks.

At that time, a ride on the “L” cost 10 cents. Similar to today’s fare system, riders were encouraged to “bundle” their fares and save money by buying three rides for 25 cents. The first version of the weekly “L” pass was introduced in 1922, which cost $1.25 for unlimited rides within the city. However, unlike today, riders paid more for unlimited passes from outlining suburbs such as Evanston or Wilmette to downtown. Chicago’s weekly pass was a groundbreaking experiment, and it changed the way working professionals would commute.

The Fullerton “L” station ticket booth in 1904

After being passed from financier to financier, all of Chicago’s railroad lines were taken over by the public Chicago Transit Authority (CTA) in 1947. Over the next few years, the CTA modernized the “L” by replacing antiquated wooden cars with new steel ones and closing rarely-used branch lines and stations, many of which had been spaced only a quarter mile apart. Much to our gratitude, the first air-conditioned cars were introduced in 1964.

Vintage “L” cars like these from 1910 been replaced

Throughout its 120-year history, Chicago’s “L” has been an important driver of Chicago’s economic competitiveness through reliable and timely access to jobs, services and recreation.

In our next post, we’ll discuss the future of the CTA, including the “L’s” infrastructure and fare management system, and how the CTA plans on modernizing one of the world’s oldest transportation systems. What are some of your “L” memories? In addition, how do you think the “L’s” history has affected Chicago?